The Premier League isn’t generally considered a division that places a great emphasis upon tactics, but this season was different. With a variety of new managers in place, there were some genuinely fascinating developments, particularly in terms of formations. Here’s a tactical review of the 2013-14 campaign.

Two up front makes a return

Two-striker systems declined in popularity over the past couple of seasons, but the leading Premier League clubs used two up front much more regularly this campaign.

The reason was linked to the slight shift away from possession play; throughout Barcelona’s reign as Europe’s best club, there seemed to be an insistence that packing the centre of midfield was the best way to dominate matches, which invariably meant only one striker upfront. As teams have begun to depend less upon possession, a two-man central midfield duo has become more acceptable, and therefore we’ve seen more old-fashioned strike duos.

Manchester City won the league with a modified 4-4-2 as their default system, with Sergio Aguero -- when fit -- supporting Alvaro Negredo or Edin Dzeko. Liverpool ran them close, and while Brendan Rodgers chopped and changed systems throughout the year, his experiments with a 3-4-1-2 and then a diamond midfield were designed to get Luis Suarez and Daniel Sturridge up front in their favoured positions.

Manchester United’s shape was more 4-2-3-1, but Wayne Rooney and Robin van Persie remain a classic strike duo, while Tim Sherwood’s appointment at Tottenham meant Spurs played a very flat 4-4-2 without being as overrun as many had predicted.

However, Southampton looked much better when they moved away from two up front -- a shape they attempted to play with Rickie Lambert and Dani Osvaldo -- and back to a 4-2-3-1. Indeed, many clubs shifted between one and two up front -- Swansea, Norwich, Hull and Fulham, for example. It’s fair to say most modern systems are variations upon 4-2-3-1, but the identity of the No. 10 -- central midfield playmaker or deep-lying forward -- defines how many strikers the manager is using.

Three-man defence revival

A related concept is the increasing popularity of the three-man defence. English football was obsessed with a 3-5-2 system just before the turn of the century, but as recently as 2008-09 it was almost unheard of for a Premier League side to play anything other than a flat back four.

This season, however, we’ve witnessed genuine variety. Rodgers’ early-season experiment with a 3-4-1-2 system clearly originated by thinking about the attack rather than the defence, and while the SAS recorded some astonishing goal-scoring statistics, the system rarely looked defensively solid.

Indeed, Rodgers used a back four in Liverpool’s first five matches with an aggregate score of 6-3, then a back three for the next five matches (after Suarez’s return) with an aggregate score of 12-7. It increased goal-scoring potential but caused problems deeper, and after a poor first half in a 2-0 defeat at the Emirates in November, Rodgers never started with the system again.

Hull City were a different case. Their situation was the opposite: they had plenty of solid defenders, but until the arrival of Nikica Jelavic and Shane Long in January, lacked attacking firepower. Therefore, they often concentrated on keeping it tight at the back by including an extra defender, and hoped for counterattacks and set pieces going forward. Steve Bruce used a 3-5-2 or a 5-3-2 in just over half of Hull’s matches, particularly when he was up against a strike duo.

That remains key -- the back three is happiest against two up front, with two players picking up opponents and the third as the spare man. The returns of the 4-4-2 and the three-man defence are clearly linked.

Others experimented with a three-man defence, although only in a couple of games -- Sunderland, Newcastle, Fulham, West Brom, Cardiff and Everton all varied their defensive system.

Crossing gets a bad reputation

It’s rare a statistic as obscure as crosses attempted receives such coverage in the mainstream media, but Manchester United’s record 81 crosses in their 2-2 draw at home to Fulham was an example of why crossing doesn’t work as a primary strategy. It’s simply too predictable, and Fulham centre-back Dan Burn’s unintentionally damning comment summed it up. “I’ve never headed that many balls since [playing in] the Conference,” he said. “We knew that was going to happen, and I was happy for them to play like that.”

Rene Meulensteen, then the Fulham manager, was more pointed in his criticism. “Their game plan was straightforward. They put crosses in from wide angles. We defended it well ... if you are well-organised, it can be easy to defend against.”

At West Ham, meanwhile, Sam Allardyce’s strategy was based primarily on crossing. Two wingers, Matt Jarvis and Stewart Downing, were told to cross the ball; Andy Carroll was the central target; and Kevin Nolan reached his knock-downs. At the start of the season it seemed unlikely to succeed, and while Carroll’s injury absence hampered the game plan, West Ham supporters’ widespread dissatisfaction with Allardyce’s playing style tells the story.

Crossing can still be useful, of course. When combined with through-balls and neat midfield play, it switches the route of attack, provides a different angle for balls into the box, and forces the defence to work across the pitch. When it’s crossing and nothing else, few Premier League centre-backs are troubled.

Sweeping goalkeepers

It’s long been apparent that goalkeepers are a side’s 11th outfielder -- their distribution is now an integral attribute -- but it’s now more common to see them sweeping out of their goal, too.

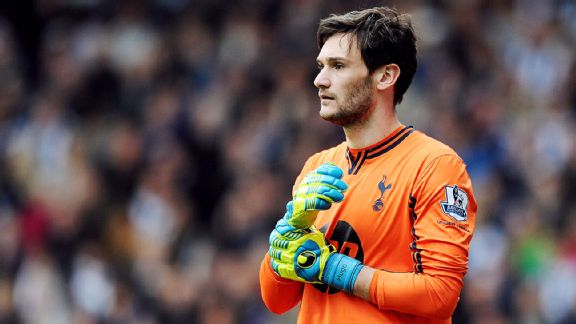

The obvious example is Hugo Lloris, a man recruited partly because he was comfortable playing high up the pitch behind Andre Villas-Boas’ aggressive defensive line. Although he made a couple of errors this season, the Frenchman’s success rate in these situations is extremely good, and he’s acted as an inspiration for others.

Hugo Lloris pioneered the sweeper-keeper movement in the Prem this year.

Tim Howard, for example, cited Lloris as a role model when speaking on U.S. television. Roberto Martinez ordered Everton to play higher up the pitch than did his predecessor, David Moyes, thus Howard was forced to change his style. In a 1-1 draw at the Emirates in December, he made a series of fine interventions when darting forward from his line.

Goalkeepers can get carried away with their footballing skills, of course. Southampton’s Artur Boruc made a comical error at Arsenal when trying to dribble his way out of trouble. He might have been better off taking the Asmir Begovic approach -- the Stoke City goalkeeper thumped the ball over Boruc after just 13 seconds of the 1-1 draw in November, an incredible goal from 98 yards.

Midfield pressing

While Barcelona’s intense pressing under Pep Guardiola prompted many Premier League sides to follow suit, the majority of sides have allowed opponents to build up play through the centre-backs without any pressure, before springing into life once the ball is knocked forward into the midfield zone.

The best demonstration of this was Chelsea’s 6-0 thrashing of Arsenal in March. David Luiz and Nemanja Matic dominated midfield with their sheer power, cutting out Arsenal’s short passing moves and winning the ball extremely quickly before moving it forward to Chelsea’s attackers to break. It was an astonishing first-half display of power.

Arsenal were also undone in this respect by Liverpool in a 5-1 defeat at Anfield, and the tenacity of Liverpool’s midfield was one of the major reasons for their unexpected title challenge. Jordan Henderson provided energy and Philippe Coutinho made some some surprisingly fierce tackles, while Steven Gerrard and Jon Flanagan stuck tightly to their opponents and attempted to win the ball quickly -- Liverpool made more tackles than any other side.

Stoke City also deserve praise for their pressing -- their early-season victory over Manchester City was a great example of how an underdog can triumph by disrupting opposition midfield play. “Everyone has to be mentally right,” Jon Walters later told the Sunday Times. “You’ve all got to have the heart and you’ve all got to do some really, really hard work. You can’t be carrying anyone, full stop.” Mark Hughes took Stoke to their highest-ever Premier League finish.

Southampton were the most impressive pressers this season -- amazingly, they recorded the highest possession in the division, despite only the ninth-highest pass-completion rate. They didn’t dominate possession because they kept the ball, they dominated possession because they won it back so effectively.

Posted by Michael Cox