When Martin Jol joined Tottenham in 2004, it was as a modestly-paid assistant manager. He stayed in a series of hotels near Spurs’ former training ground in Chigwell, moving from place to place to keep getting discount rates. His wife and young daughter were in tow; they needed a proper home. Yet Chigwell was expensive. Daniel Levy stepped in.

A house was for sale on the road where Levy’s parents lived and though he had a football club to oversee, Levy took charge of negotiations, going back and forth until talking the owner into selling for a knockdown price. Seventeen years later, Jol still has the house and Levy the knack for advantageous deals. This personal touch, which he uses to run Tottenham, gets overlooked in portrayals of Levy as an unfeeling numbers man.

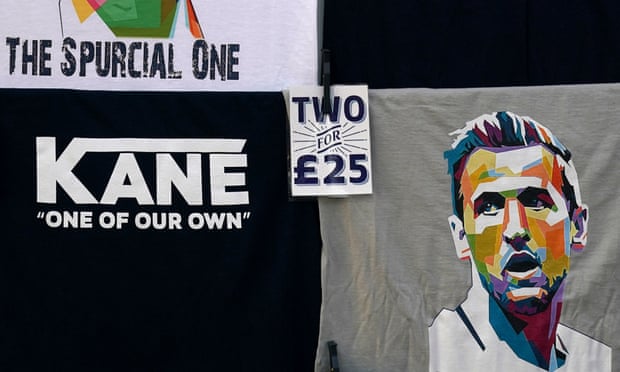

After 20 years in his role, and having given next-to-no interviews, the Premier League’s longest-serving chairman is much-discussed yet little truly known. He remains the inscrutable figure near the centre of English football and could be about to pull off another coup: keeping Harry Kane

It is increasingly likely Kane will be Tottenham’s player for at least another year. Manchester City’s money was expected to talk, but Levy feels City have left it far too late in the transfer window to come to the table for a talent it would be so hard to replace. He has his valuation of Kane, which is far beyond the £100 million City signalled they would pay, and Levy doesn’t budge on valuations.

There has been no negotiating between the clubs in recent days, despite reports, and it is thought Kane is close to accepting there will be no exit this summer. “Daniel is unbelievable,” says Jol of Levy’s tendency to get his way. “How does he do it? He is like Napoleon. There is always a strategy. He waits and waits and he is tough. Others try to wait but at some point you get bored and go a little soft. Daniel will wait longer than you.”

The Kane saga comes at a pivotal point in the development of the club Levy helped acquire by wearing down Sir Alan Sugar into selling the controlling share for a larcenous £22 million in December 2000. Levy represented the English National Investment Company (ENIC), an offshore investment firm bankrolled by the billionaire Bahamas-based currency trader Joe Lewis. Levy, the whizzkid son of a friend, proved his acumen to Lewis soon after ENIC’s formation, when he paid £6 million for 4% in an internet start-up then sold the stake for £160m.

Initially, ENIC was supposed to focus on textiles but soon moved into football. Levy was taken by a great-uncle to his first game, Spurs v QPR, wearing a rosette, aged around eight. He later recognised football’s potential to grow in value but realised that “a football club is one of the hardest things to run” as he told Cambridge University’s newspaper last year.

State educated, Levy admits being unathletic at school (his favourite sports were skiing and abseiling). At Cambridge he eschewed student partying to focus on his degree. “I thought I had been given a great opportunity and was determined not to mess it up.” He graduated with a first in land economy, where you study not just the value of land but the politics around developing it. He started talking about rebuilding White Hart Lane, and delivering world-leading facilities, in 2001.

It took seven years and three planning applications to construct the Tottenham Hotspur Training Centre in Enfield, and a decade of work, including 80 separate property deals, to open the £1.2bn Tottenham Hotspur Stadium in 2019. Spurs’ valuation has increased almost 100 times, in his tenure, to over £2bn with revenues hitting a record £460 million before the pandemic.

“The smartest transfer policy in football, the best youth system, probably the best training ground and the world’s best stadium,” is how Crystal Palace chairman, Steve Parish, evaluates his rival’s work.

Transfer trading has underpinned Spurs’ rise. Unique to major clubs, they have grown without owner-funding – with Levy (who holds 29.9%, with Lewis holding 70.6%) raising every penny he spends. In 20 years, Spurs’ net spend is more than £1bn less than City’s, over £700 million less than Manchester United’s and almost £450 million less than Chelsea’s. However, constructing the new arena has left the club with £831m of debt (albeit mostly in long “mortgage-style” loans) and Covid saw it last year post a first loss (£68 million) since 2012.

Against the backdrop, Jol – Spurs manager from 2004 to 2007 – believes the old Levy would have cashed in on Kane but today’s Levy may not. “He has grown into his role,” says Jol, meaning that what started off as business has become something in which Levy invests emotionally, like a supporter. His four children, particularly eldest son Joshua, are Spurs fans and, according to someone who was a key Spurs employee for more than a decade, “he definitely ‘feels’ it – especially the north London rivalry and need to finish above Arsenal.”

In Levy’s office at Lilywhite House (he has another at the training ground) is a former street sign from Paxton Road, on which the old White Hart Lane stadium sat. On the wall are family photos and gifts from friends.

His ability to listen and absorb information is what most impresses those who have worked with Levy. He is a quiet man “but can be blunt and honest”, says the former employee. He reads every email he is sent, and even those where staff reply on his behalf. Though he cares little for public perception, Levy, now 59, is said to be across everything that is said and written about Spurs in the traditional media and on social outlets.

His grasp of detail is formidable. On his early-morning commute to work from his estate in Hertfordshire, Levy changes his route to drive whichever one of his club’s properties or projects is on his mind. He is a member of a club WhatsApp group with senior aides and if anyone spots something out of place at a piece of Spurs estate they take a photo and share it.

Recently Levy has been driving past a plot on which he plans two artificial pitches for use by the community but also for scouting youngsters. With most clubs now siting academies in leafy suburbs, hard to access for inner city kids, Spurs believe they can steal a march by building this new facility.

Levy chooses unusual ways to reward staff. When Jol took Spurs back into Europe for the first time in seven seasons, Levy bought him a silver grey Porsche and when he achieved back-to-back fifth-place finishes (Spurs’ best league performance in 25 years) he took Martin and wife Nicole to dinner at the Dorchester. There was a charity auction in which the star prize was Christmas dinner cooked personally at the winner’s home by Gordon Ramsey, and Levy exclaimed, “I’ll get that for you, Martin”. However another lot was a piece by the leading English sculptor, Sean Henry, which Jol – an art collector – really wanted. He asked Nicole to have a subtle word and went to the toilet and when he returned Levy had bought the sculpture – for £40,000.

“It’s very nice,” says Jol, “though I had it valued last week and it’s worth £12,000. It’s a little figure of a man…it actually looks like Daniel.”

Gifting should not be confused with largesse. Jol notes that Levy preferred presents to paying bonuses and says, “it would be wrong to describe him as a ‘warm man’ – he’s a businessman – but he wants to make you feel good, if things are going well. If things are not going well, it’s different. But I had a good relationship with him.”

Jol still likes Levy despite being sacked summarily (he was in the dug-out during a game when he was told) and the same is true of Mauricio Pochettino, the boss Levy was closest to. They went on wine-tasting mini-breaks together, retreats at Levy’s home in the French Alps and a bonding trip to Argentina which involved quad-biking, paintballing and a river journey during which the boat capsized and “Poch” pulled his chairman to safety. At the training ground they would often eat together. They still text.

After José Mourinho’s acrimonious departure, and the messy search for his replacement, it remains to be seen what bonds Levy will establish with his new manager, Nuno Espírito Santo. But Nuno is also a quiet, publicity-averse man with a human side hidden underneath a hard exterior. Like Levy, he’s a listener: he is said to be fascinated by Tottenham’s motto, To Dare is To Do, and has been asking key people what it means to them personally.

He, and new sporting director Fabio Paratici, have already been allowed to reshape the squad, recruiting Bryan Gil for £22.5million and Cristian Romero on a year’s loan from Atalanta with option for a £46.7million permanent deal. Spain’s Pau Torres is the next target. Contrary to the perception that Levy wants to influence who the club signs, allies say the opposite is true. However, he does take charge of negotiations and is “the worst to deal with” if you want to bargain, confides one manager. Sir Alex Ferguson said dealing with the game’s most stubborn negotiator was “more painful than my hip replacement”.

One agent who has sat opposite Levy says his method is simple. “He has a number in his head and just doesn’t deviate. He just relentlessly says, ‘that’s it’ while delivering his logic for why the valuation is right. Rebecca Capelhorn, a lovely woman [Tottenham’s director of football administration and governance] often sits in the middle of the process and will come back to you politely: ‘No, I’m afraid Daniel won’t do that.’”

When Spurs signed Pierre-Emile Hojbjerg, Levy decided – given his age and length of contract – he was worth £15 million and when informed Everton were willing to pay £18 million just dug in, pointing out Spurs was the Dane’s preferred destination. He got Hojberg for £15 million – though the technique doesn’t always work. A year ago he offered Brentford a “take it or leave it” £20 million for Ollie Watkins and they left it, with Watkins going to Aston Villa.

But Levy sticks to his valuations with such conviction, says the agent, “that you can come off the phone saying ‘he has a point’ – before you pull yourself back.” Everyone, from allies to those who have been on his wrong side, agree his guiding principle is “what he sees as best for Spurs” and sometimes transfer sagas are simple: if that means Kane not leaving, he won’t leave.